Shanghai Glam // The History of The Qipao

What is a Qipao? Discover The History Of This Gorgeous Garment

When someone asks you to imagine a Chinese dress, a qipao (旗袍 qípáo) is what often comes to mind.

Maybe in a smoky, art-deco styled nightclub in 1930’s Shanghai?

Or worn by an actress in a 1960’s Hong Kong movie?

In this blog, we will take a look at the origins and history of the qipao.

We will also see how the qipao was influenced by the culture of the time, and how it indeed also influenced the culture and society.

History of the Qipao – Three Theories

History of the Qipao – The Roaring 20’s in Shanghai

History of the Qipao – How Has it Evolved?

History of the Qipao – Feminism and Equality

History of the Qipao – In Later Years

History of the Qipao – Three Theories

The qipao has an interesting history, involving the rise and fall of the Qing dynasty (1644 – 1912), the Republic of China (1911-1949), women’s liberation, opening up of China, westernization, and a revival in the 1980s. As we will see, the qipao might even go as far back as the Han Dynasty (221–206 BC)!

The exact origin of the qipao is not agreed upon. There seem to be three main competing theories.

What is interesting is what these three theories have in common.

They all agree that the qipao was influenced by foreign clothing. However, the exact source and degree of influence is under debate.

Let’s take a look at these theories:

Theory 1: Qipao and the Manchus

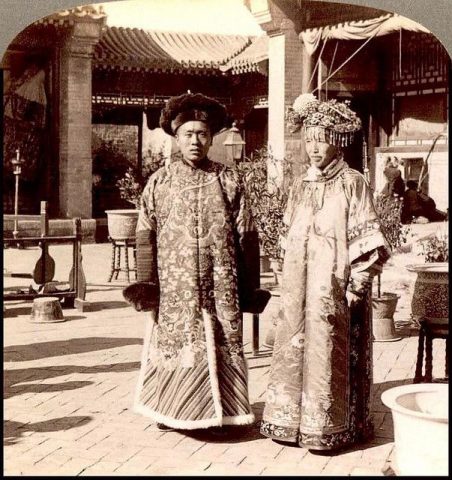

The first theory is that the qipao is heavily related to the Manchu robe called “chángpáo” 長袍 which was similar for men and for women.

During the early Qing dynasty, all Han Chinese men were required to wear Manchu style clothing.

Later, only government officials and men of a certain social class were required to wear Manchu style clothing.

The male version was called 長衫 chángshān, which by the way of Cantonese (chèuhng sàam) we got the English name “cheongsam” for the women’s dress.

What is interesting here, is that due to the clothing requirements for men, men’s dress style became very Manchu in a relatively short period of time.

Even among the men who were not required by law to wear these clothes, the Manchu style became very popular.

The qipao was the female version of the chángpáo robe and took a long time to gain acceptance with Han women. Women’s clothing at the time was much less influenced by the Manchus, in no doubt due to there not being any legal requirements for women.

The early Manchu qipao was quite different from the qipao we know from China today. The Manchu qipao was not body-hugging but was indeed baggy specifically to conceal the wearer’s figure.

Theory 2: Qipao in Ancient China

The second theory claims that the qipao existed in China since the Western Zhou dynasty (1046 BC-771 BC), more than two thousand years before the Qing dynasty.

According to Yuan Jieying (袁杰英) author of the book “Chinese Cheongsam” the qipao shares several similarities with a narrow cut, straight skirt which was popular with women during Western Zhou.

The qipao also shares some similarities with a long one-piece dress which was popular with women during the Han dynasty.

It is then likely, according to this theory, that these ancient dresses incorporated some ideas and features from the Manchu dress to become the qipao that we know of today.

Theory 3: The foreign connection

The third and final theory, proposed by Bian Xiangyang (卞向阳) in his book “An Analysis on the Origin of Qipao”, is that the qipao had its birth during the days of the Republic of China, when people were open to, and accepting of foreign influences.

The qipao thus being a mishmash of western clothing styles combined with traditional Chinese styles and fashions.

In particular, the similarities to the waistcoat, and the one-piece dress which was popular with western women at the time are being emphasized to support this theory.

China, and especially Shanghai, went through a phase of opening up during the days of the Republic of China.

Western influence cannot be ignored when talking about the qipao, the question is, however, how big was this influence exactly.

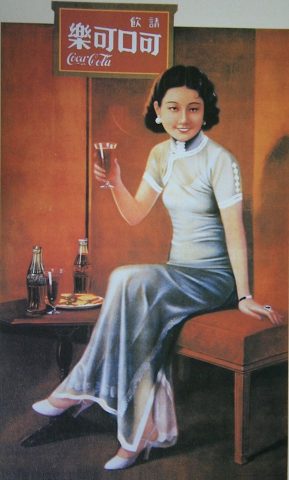

On the right we can see an advert from the 1930’s in which a Qipao is worn by a girl.

Significantly the advert is for a rather large brand, Coca Cola giving the Qipao huge exposure!

History of the Qipao – The Roaring 20’s in Shanghai

The first theory, about the Manchu dress, seems to have the widest acceptance today. One reason for that might be how the qipao gained popularity.

One of the early adopters of the qipao was Madame Wellington Koo, the first lady of the Republic of China. Her sense of style and fashion was admired far and wide, and her style often incorporated Manchu clothing, adapted to modern times.

Madame Koo is also widely believed to have popularized the longer side slit as is commonly seen in modern qipao’s, before her the slit usually went up to the ankle, but not higher.

The tighter fit, higher cut, and the higher slit were all due to a wish for a more modern, and more westernized version of the qipao.

The ladies of high society with Madame Koo at the front popularized the modern qipao in Shanghai in the 1920’s, 30’s and ’40s.

In Shanghainese the qipao was called zansae which translated simply to “long dress” in Mandarin it was called chángshān and in Cantonese chèuhngsāam, finally ending up as “cheongsam” in English.

History of the Qipao – How has it Evolved?

It is also interesting to look at how the qipao and it’s accessories evolved alongside each other.

In the early days, the qipao was worn exclusively with pants. One of the biggest innovations in women’s fashion in the early 20th century was indeed the nylon stocking.

The higher cut and the higher slit was used to show off this new fashion item.

Today, the qipao is often worn with bare legs. The Vietnamese traditional dress, Ao Dai, is similar to the qipao and is exclusively worn with pants.

As western fashion changed, so did the qipao. Sleeveless, high neck versions became popular, some qipao’s imitated western ball gowns with for example black lace at the hem.

By the late 1940s the qipao was available in a wide range of colours, cuts, materials and with various accessories.

The communist revolution of 1949 ended the popularity of the qipao in Shanghai and the mainland, but emigrants to Hong Kong and Taiwan brought with them the qipao where it remained popular. Since the 1980s, there has been a qipao revival in Mainland China where the qipao is used as a fashionable party dress, including in an official capacity.

History of The Qipao – Feminism and Equality

One of the factors that helped with the qipao’s popularity in the 1920-1949 period in Shanghai was the push towards more gender equality and women’s liberation.

The Qing dynasty was oppressive towards women. After the dynasty’s fall and the creation of the Republic, women became emboldened to cry out for liberation and equality.

No longer should women be forced into traditional gender roles as per Neo-Confucian thought, be forced to bind their feet, or be required to have long hair.

One way this protest was done was by women wearing the traditionally male robe, the changshan.

From all the way back to the Han Dynasty and up until the overthrowing of the Qing dynasty in 1911 men’s robes were one piece, while women’s robes were two pieces.

Women were forbidden from wearing one-piece men’s robes, but this was about to end.

In the early days of the Republic, the qipao was seen as a political statement. That statement was a promotion of gender equality, and the early Republic qipao’s were often dyed in cool, restrained colours.

After the fall of the Qing dynasty, China opened up to the world again, young Chinese people went abroad to study, and the ports were again opened up to foreign trade.

This resulted in an influx of foreigners who with them brought new ideas and thoughts, as well as new western clothing. The qipao was caught up in this perfect storm of societal upheaval and new ideas, and thus got influenced by ideas and fashions from far and wide.

By the 1930s the qipao had permeated the mainstream and was no longer a political statement. Women of all ages and all social class wore qipao’s, both celebrities, and working women.

It was in the ’30s and ’40s that the qipao really came into its own.

Less baggy, and more form-fitting, shorter, from ankle length to above the knee, and new styles of collars and sleeves were added as well. Resulting in what we would consider the modern qipao. No longer was the qipao a baggy dress to conceal, or a political tool.

Now the qipao was a modern, fashionable dress for the new generation of Chinese women.

History of the Qipao’s – In Later Years

From 1949 and to the 1970s the qipao was not very popular in Mainland China due to the political reality of the times.

However, working women in Hong Kong and Taiwan used qipao inspired clothes when going to work, usually tailor-made out of cotton or wool, and with a matching jacket.

This, however, was replaced by western style office clothes in the 1960s and 1970s. These western clothes were seen as more practical and more modern, and since they did not need to be tailored, they were often cheaper as well.

The qipao revival in 1980’s mainland China, which we mentioned before, was backed by the Chinese government at the time.

It was made explicitly clear that the qipao was part of Chinese culture and tradition. Today you can still see qipao’s being worn in formal contexts such as weddings, galas, or even official diplomatic events.

You can also see the qipao in certain service industries, some restaurants, hotels, and airlines use qipao, or qipao inspired uniforms for their female staff.

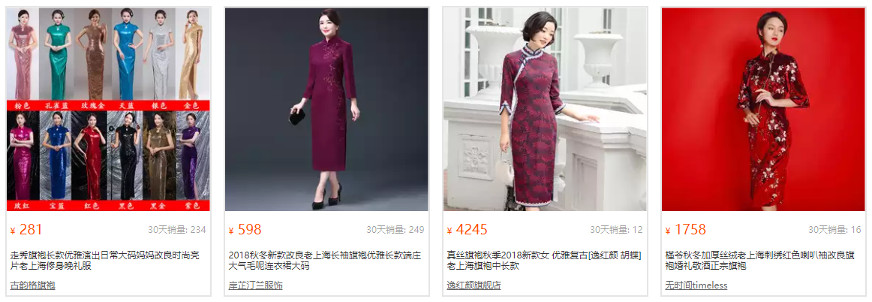

Qipao’s are readily available for sale across China, both online and offline. Prices vary widely, Ornately decorated qipao’s made from the finest silk by a high street tailor in Shanghai can easily cost tens of thousands of RMBs.

On the other hand, a quick search on Taobao can net you a qipao made out of silk for a few hundred RMBs, maybe less if you shop around.

Qipao’s from synthetic fibers can be had for 20 RMB or less.

Did you know you can also buy a Qipao on Amazon! There’s loads to choose from including this one where you can select your preferred design.

Please note the link above is affiliate link. LTL Mandarin School take a small cut of any sales made, with the rest going to Amazon and the lister of the product.

We hope you enjoyed our blog about the history of the Qipao, have you ever owned a Qipao? Have we inspired you to get one of your own? Drop us a comment below!

More clothing related blogs:

Traditional Chinese Clothing

Want to find out even more about traditional Chinese clothing? Then have a look at our blog about other traditional garments.

Clothes in Chinese

Learn all the vocabulary you need to talk about clothes in Chinese. Guaranteed to make shopping on Taobao a whole lot easier!

Qipao – FAQ’s

Are Qipao and Cheongsam the same thing?

Yes they are the same item of clothing.

The Qipao is the Mandarin Chinese name for the dress. The Cheongsam is an English derivation from the Cantonese name Cheuhngsaam.

Can I buy a Qipao online?

Absolutely. Qipao’s come in all kinds of styles, designs and colours and there are thousands available online for all kinds of price ranges.

What are some of the most traditional Chinese types of clothing?

Qipao’s are one of the most traditional items of clothing you could come across in China.

Others include the Hanfu, the Tang Suit and the Zhongshan Suit.

Want more from LTL?

If you wish to hear more from LTL Language School why not join our mailing list.

We give plenty of handy information on learning Chinese, useful apps to learn the language and everything going on at our LTL schools.

Sign up below and become part of our ever growing community.

FANCY LEARNING CHINESE ONLINE? Why not sign up to a 7 day free trial of our Flexi Classes.

![[𝗢𝗟𝗗] LTL Shanghai Logo](https://old.ltl-shanghai.com/wp-content/sites/3/logo-ltl-header.png)

4 comments

[…] Cheongsam/ Qipao style dress is said to originate from Qing Dynasty times (17-20th centuries), in particular from […]

[…] in China the bride would wear one dress which would normally be a traditional cheongsam (旗袍 qípáo) or jacket and skirt, all in red. The groom would wear a traditional Tang suit […]

Gorgeous piece of clothing!

You aren’t wrong!